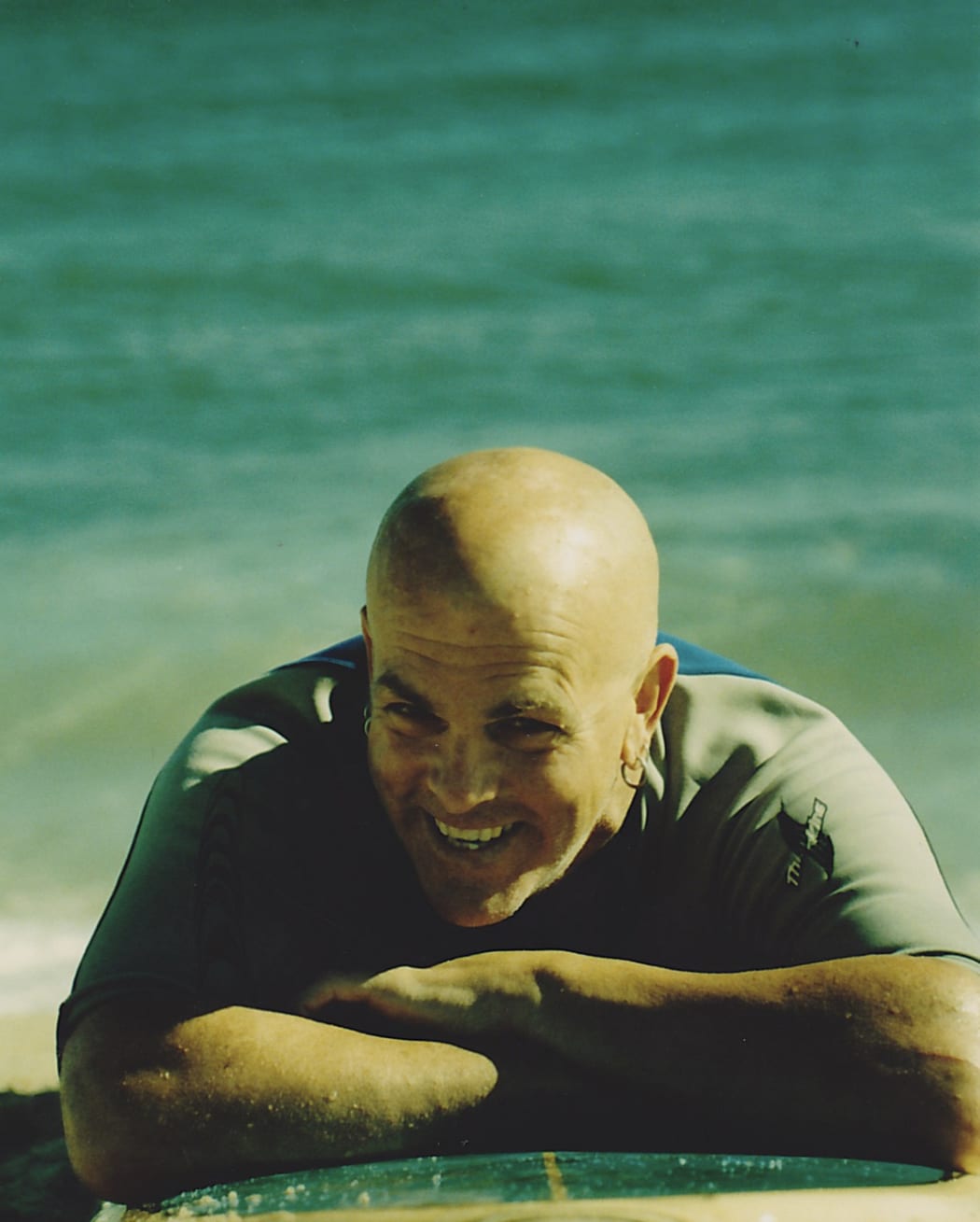

Late in the night of September 1st, my father, Michael Stuart Gaillard, Sr., passed away due to complications of COPD and Congestive Heart Failure. He was a kind, compassionate, gifted, iconoclastic man who touched many. He was a world-class cook, an extraordinary surfer, an avid golfer, a uniquely intuitive healer in his capacity for a time as a massage therapist, and a powerful, imposing, yet gentle physical presence. In his younger years he was stunningly handsome, with piercing light blue eyes, a chiseled jaw, and a beguiling smirk. He was a visionary of sorts with great talents and lofty ambitions, but organizing his thoughts and taking first steps to execute them proved nearly impossible.

Articulating improbable dreams without a clear plan nor the tools necessary to achieve them became a pattern. The inertia of potential led to psychological paralysis, matched by and probably manifested in chronic physical pain that plagued his later years. Trapped in a gyre of pain and regret as an older man, he spent a lot of time thinking about how others stood in the way of his success, and first in that line were usually the women he partnered with on whom he depended. My father became a serial monogamist, married and divorced four times and in a few other years long relationships. He could never be alone with himself but nonetheless always felt alone.

This wasn’t entirely his fault. His parents, Gwen and Harold Gaillard, were the owners of The Opera House Restaurant, among the first fine-dining establishments on Nantucket (it opened in 1945) and a cosmopolitan outpost that became the cultural epicenter of the town for 40 years. It was more than just a restaurant. It was the place to be on Nantucket, and my grandparents were the gatekeepers. But behind the scenes it was never easy—my grandmother was always plugging holes in a dam. When my father was a young adult in the early 70s, his father—a WWII Navy veteran, and a handsome, charming, cultured man who drank way too much and had a gambling addiction—committed suicide by jumping off the Nantucket ferry with bricks in a suitcase tied to his neck. In many ways this abandonment kept my father from progressing as far as he could or should have. He never escaped this shadow. That young man, that boy, remained with him, frozen in time, even at the end.

LEMONS NO. 15165, 38.5 X 31 IN. (97.8X 78.7 CM.); 2022

Despite being mostly estranged for the past 12 years, we were inseparable during my teens and early twenties. We connected over not fitting into a mold—a prominent theme of the Gaillard narrative that was at times something to celebrate, but over the years became isolating and burdensome. After having had a fairly lonely childhood out in California, I returned to Nantucket with my mother when I was 13. I made up for lost time with my father and spent nearly every free moment I had with him, much to the chagrin of my mother, who was rightfully fearful of how his tendencies might influence me.

For a few beautiful years, the imaginary, impossible father I had created from across the country met with the man it had replaced and that illusion burned brighter than reality, obscuring his flaws from my sight. We both benefited from this projection. I saw his best self in everything he did and modeled myself after him and he was proud of the man I was becoming in his likeness. Whether surfing hurricane swells and trading waves off the coast of Nantucket to dominating on the pool tables at the Chicken Box over a secret pint of Guinness before I was of age, we were inseparable for a few beautiful years. At our best we reveled in our mutual rejection of societal norms and expectations. While he couldn’t engage in all that I did anymore, I jumped at any opportunity regardless of the risk involved, and he lived vicariously through me, affirming my actions while most others questioned them. Despite the eventual fallout from many of these decisions, during that time my freedom and his affirmation empowered me, while he enjoyed bearing witness to my rebellion. Even though the consequences were significant, this period was a rare gift that, even when things were at their worst, we both cherished and felt very fortunate to have had. And I do still.

The illusion I had created and he benefited from was bound to fade. As he grew older, his body started to fail him while I began to figure out my life, and our stories diverged. I had fallen in love, gotten married, and started to shape a life and career with my art. In pain almost constantly, his grievances mounted. At the time he was in the late stages of his fourth marriage to a woman more than twenty years younger than him, with whom he had another son when I was 21. My brother never had the dad I had. My father did what he could to be there for my brother in the early years, and he loved him very much, but by that time in his life, his pain and frustration were constants, and it was difficult to see clearly through it.

The growing divide between my father and me stemmed from the contrast between the flawless superhero I envisioned in my youth and the person I was coming to know in adulthood. My parents divorced when I was four and my mom moved out to California with me when I was five, to start a new life with a new man (Frank, an artist and iconoclast in his own right whose influence on me was significant), far away from Nantucket, her mother, my father, and the life that had come to suffocate her. Obviously it was hard for me to understand why that happened, and I blamed my mother for abandoning my father. I told myself a story that, with little empirical evidence to the contrary, was easy to live with. My father assumed the throne in my mind and my heart, and when I saw him I made sure that illusion wasn’t broken.

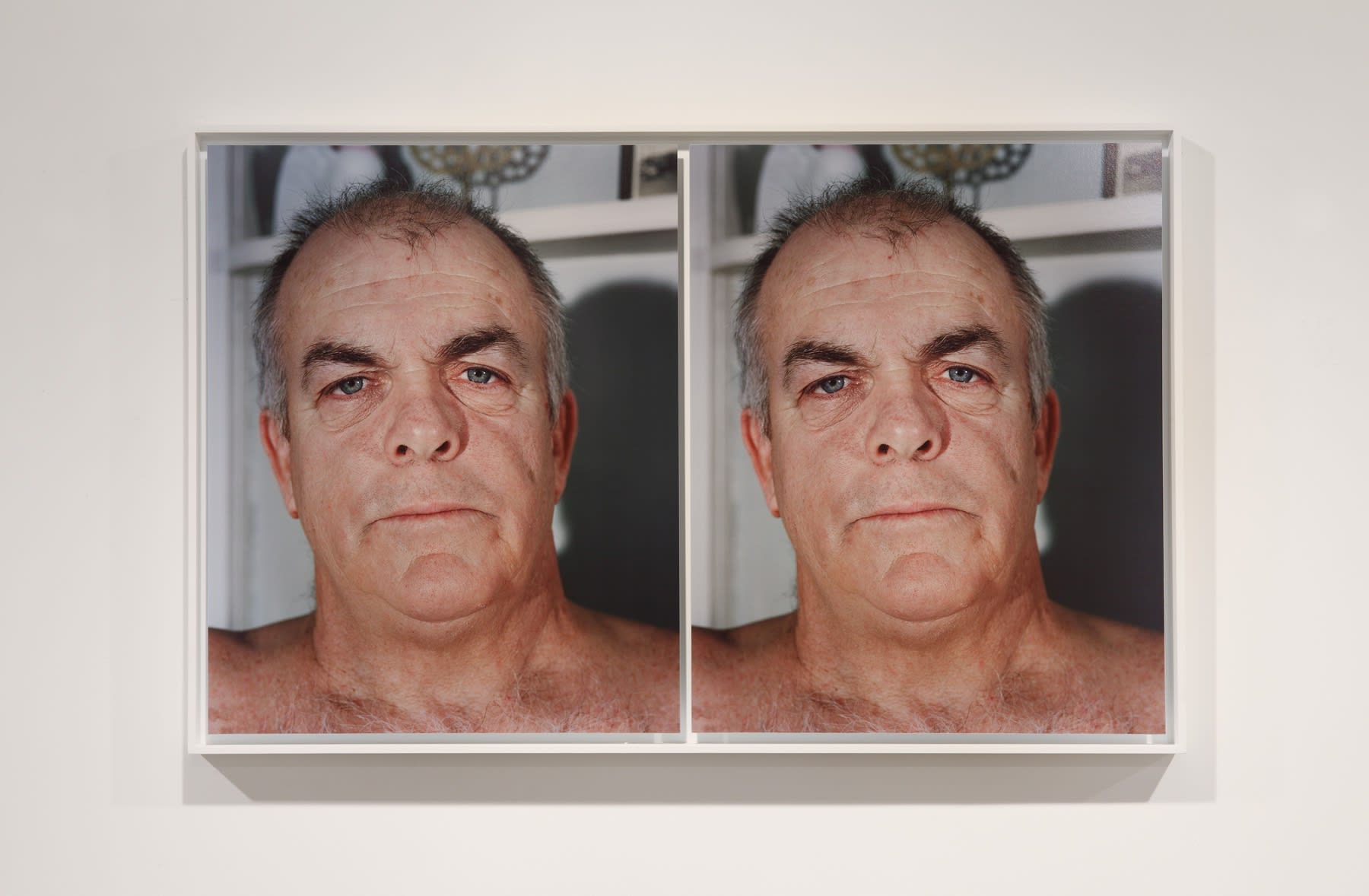

The work I made during grad school circled around the idea that we are both the subject and the object of the stories we tell ourselves to understand who we are. We are the child and the parent, the character and the author, the image and the original. This piece below, SonFather, was instrumental in me finding my path at that stage in my life. Ironically, a misunderstanding of my motivations, which I to this day stand by, compelled my father and his partner to cut ties with me. So began our estrangement, one that caused him to miss the birth of our boys and many other momentous events and transitions in my life and career.

sonfather, 40 x 62 iN. (101.6 x 157.5 cm.); 2009

During that period, I lost contact with much of what was special about him, our relationship, and aspects of his influence that, together with my mother's facilitation, made my early successes possible. I had been abandoned by the person I once revered above all others, and that transgression proved impossible to overcome for many years, even after he returned to my life one dappled afternoon in September.

I was sitting at my desk in my gallery in Nantucket facing the large window that overlooked a little backyard bathed in piercing late-summer light. Many of you may recall the space—glossy bright white floors and warm white walls with my landscapes hanging around the space. I heard footsteps creaking the floor in the front gallery and, as they approached the back room, a familiar, booming voice echoed dramatically, “MICHAEL...GAILLARD...STUUDIOOO.” I turned to see my father standing in the doorway of the backroom of my gallery, deeply tanned with his wry smile, pride sparkling in his eyes. “Hello, son.” I immediately stood up and we embraced heartily, wholly... for that instant everything was forgiven. But it didn’t take long for the illusion to be broken.

He sat down and we started to talk. He spoke of his overwhelming pride in me. A marvel, I was. The profound beauty of my work and the success of my enterprise a testament to my having been able to break the cycle. To transcend the “Gaillard curse,” whatever that meant. The light shining through the leaves outside tinged the white room green, the leaves’ shadows fluttering through the space, dancing on the walls, my art, the floor and his sandals, tattered and dusty. I noticed the signature Birkenstock tread pattern on the floor behind him. His long cracked toenails and dirt beneath them. A few open wounds on his feet and legs. Tobacco stained fingernails. These details, his lofty language and grandiose plans evinced what had led him there, then.

It turned out that his partner had broken up with him 3 months prior. He had been living in woods south of Boston for the summer, and managed to sneak onto the ferry to Nantucket to find me. He was looking for help, for shelter, for financial support and ideally, forgiveness and redemption. He was also, it seemed, in the midst of the early stages of a manic episode.

He was exhausted and I still had some work to tend to, so I put him in my car to sleep. He slept for hours before I brought him to my summer rental house which I had for one more day before closing the gallery for the season and returning to my family and home in Brooklyn. He showered for what seemed like an hour, cleaning months of dirt from his pores. He came out grateful and contrite, willing to defer to my lead, for I was all he had anymore. But I couldn’t help myself. I wasn’t ready for what came next. I was suddenly overcome by a primal rage that welled up and burst forth. I screamed at him, slammed walls, stormed around the house, my voice became hoarse as I plumbed the depths of his betrayal and how it damaged me to my core. I surprised myself. I was never the same after that night. Something in me fractured. I think I’m still repairing the wound that opened up that night.

At dawn the next morning I was finishing cleaning the house before I handed over the keys. I was exhausted and deflated, but in some way I also felt a sense of relief. I had no energy to challenge him anymore, nor did I feel I needed to. We joked around a bit. The air was light. My dad was helping by clearing out the pantry and putting every bit of food into a giant garbage bag. I figured that was something easy I could do for him. Little did I know he was also clearing out the house of a number of other items that could prove useful to him. He had always been a hoarder of sorts. It was endearing mostly, and as long as you didn’t mind a bit of chaos, harmless. He’d save everything that had potential use value, even if he didn’t know what that use might be down the road. The Nantucket dump has a Take-It-Or-Leave-It pile that offers some extraordinary finds given the milieu that keeps it stocked. My dad also had a bunch of like-minded friends who would frequent this trove, so I decided the best strategy would be to drop him off there before I left the island. I thought if I left him there he’d have a good chance of encountering an old friend who might lend a hand. He agreed that this was a sound strategy. I dropped him off outside the chain link gate an hour before it opened, the dense fog quickly obscuring him and his big black garbage bag in my rearview as I drove away.

A week or so passed and I returned to the island. Outside my gallery I encountered an old surfing buddy, Richie, who asked ominously if I had seen my dad recently. I told him I had a week ago and he filled me in on what he and others had witnessed since I left him at the entrance to the dump. My dad had set up camp at Cisco, the part of the beach called the end of the road, about a quarter of a mile west of the main beach where the new parking lot is. It has always one of the most popular beaches on the island, and the place where he had learned to surf in the early sixties. There he met his first love as a teenager, when he ruled the water for a time. He was one of the first surfers on the island and surfing remained central to his identity throughout his life, including when he taught me at Cisco thirty years later. But as you can imagine, one doesn’t set up camp on a popular beach on Nantucket, especially in season. I knew in he felt the island owed him the leeway to give him this freedom. He wasn’t entirely wrong, as the police were a little more patient with him than they would with others, giving him a few days to figure it out.

As reluctant as I was to go see what was going on, I knew I had to. I was, of course, conflicted. Part of me wanted to drop my emotional baggage and give him everything he needed, while the other couldn’t overcome the anger and sadness I felt. But there was always something I could do, and so began my journey on a fine line between what I could and couldn’t offer him. Opening up only to close myself off, time and time again.

I parked down the beach from where I was told he had set up camp, needing a bit of a buffer from the eventual confrontation. It turned out that there were perfect little waves rolling in that afternoon, so I decided to catch a few to center myself before confronting him. Without a breath of wind, the water was so reflective you could barely tell where the water met the sky. I saw a line of smoke on the beach on the horizon, and a silhouette of a man, hunched, walking slowly back and forth from water’s edge to the fire. I knew that limp, I could tell he was in more pain than when I had left him. With each wave I took I let the current pull me further west, down the beach and closer to my father. A light mist glowed pinkish-purple on the surface of the water as I took a wave to the beach, riding right up to where my father had planted himself, his encampment situated just a few feet away from a young family with matching monogrammed chairs catching one of their last days of summer, clearly unsettled by their neighbor, but committed to keeping the vacation routine for which they had paid dearly.

markmaker (reclining), 10 x 12 in. (25.4 x 30.5 cm.); 2010-2023

I walked up board in hand, the chill of the approaching fall starting to nip at my skin as the pastel light dwindled. His campsite took up at least 30 feet in diameter, with areas designated for different potential uses, as though he were planning to stay for quite some time. Some pieces of cracked bluestone were cobbled together in a path from an entry he had lined with pine boughs to the fire pit. Just inside the entrance were two rusty sets of mismatched golf clubs. He had a couple inner tubes, a football, two frisbees, some lengths of heavy rope, some piles of fishing line and another pile of netting, a few buoys. There were a bunch of empty liquor bottles he had found and stacked as a sculpture of sorts, he didn’t drink anymore and hadn’t for years but he was drawn to the different colored bottles and the way the light passed through them, figured it brightened up the place. In the ‘kitchen’ were a handful of pots I recognized from the rental house I had left, and one large pot was bubbling on the fire.

My father was lying beside his fire, propped up on one arm while stirring the pot with the other. Without hesitation, as though he’d been waiting for me to emerge from the ocean before he even saw me, he rose up and asked, “Want a cup of chowder? It’s a bit like your grandfather’s.” My grandmother wrote a cookbook entitled “Recipes With Love” in which there is a recipe for a fish chowder that my grandfather loved, and the accompanying pen and ink illustration is of a fish with huge, bushy eyebrows and glasses, with that same knowing half smile my dad had. I wondered where he had gotten the money for all these ingredients… it turned out he had borrowed the money from our Chilean friend Hector who we had played pool and partied with at all night beach raves back in the day. He bought the food for a party that only my father attended. He grabbed a used paper coffee cup from beside him, filled it, and handed it to me with a whittled piece of wood for a spoon. I bent over and received the cup between my two hands, still wet, plopped down into the sand and brought the cup to my mouth. In a reverie, I sipped the chowder while pushing the pieces of lobster, halibut, clams, potatoes into my mouth with the whittled stick. As I sipped the chowder, time stood still.

Bathed in the purple glow of the last minutes of the day, my senses were overtaken by the sheer perfection of this dish he had prepared. Balanced and fresh, perfectly seasoned with a hint of spice, thick but not heavy, rich and sweet but not cloying, it was smoky on the nose but not on the palette, I can’t even begin to describe how perfect it was, as good as anything you could get at a three star restaurant in Provence. It was an ode to Nantucket and our lineage. His fire sending smoke signals to those who came before, inviting them to the feast. We were hedonists. Gourmands, he always liked to say. The Gaillards loved to eat and loved to live, a bit too much, always. This chowder was the perfect counterpart to the color, light and air surrounding us. I devoured it barely taking a breath or making a sound, my father watching from across the fire, thoroughly contented in the moment, no doubt aware of how fleeting it was. I tilted the cup, scraping the bottom to get the last succulent mouthful, only to find the last bite full of sand. I couldn’t help but laugh.

Until my father passed, I’ve found it difficult to see beyond the person who removed himself from my life. When he chose to leave my life, that man at that moment was what I saw. I couldn’t see both at once. I allowed my memories of all that was wonderful about him to be overtaken by his decision to remove himself from my life. The complexities, the nuance, the continuum of our narrative had compressed and ossified into the image of the broken man who disregarded me. But as time passed I couldn’t hold on to the rage anymore. He was both the man who betrayed me and the boy under a table at the Opera House, the soul surfer, the hustler, the chef, the healer, the lover. He was all these people and more.

LEGACY; 32 X 80 IN. (81.2 X 203.2 CM.); 2010

In unpacking the loss of my father, I once again started to think about how my relationship to and perception of him related to my art practice. But this time it has been less abstract and more practical than it was in graduate school. My father never felt like he was part of a community. Always an outsider looking in, he liked to talk about himself as a shaman—indispensable and revered, but necessarily solitary. I have at times told myself the same story, but instead of a shaman I was an artist. My wife, Brett, would remind me that in fact, I am far from alone. I am surrounded by wonderful people who I love and who love me. I am not my father. I have always been lifted up by my friends throughout my life, and these relationships have played a huge role in helping me become the person I am today.

While he had very real obstacles to overcome, my father set such high bars for himself that he never got off the ground. The small steps were too small, too far, too inadequate for the scope of what he envisioned he deserved. He could never escape his own narrative. Now I acknowledge that I have done the same thing for quite some time. Always waiting for the perfect moment, the perfect manifestation of my vision before I unveiled it. But of course it’ll never be perfect. I see now that the desire to produce something perfect is really a protective measure. Looking for validation but fearful of failure, the safest choice is to wait. That's what my father did until doors that may have once opened rusted shut.

In my younger days I spent a lot of time addressing my story and the language I employed to render it. I focused on myself without really looking outward, thinking that my experience spoke to a more universal condition. Now, with two sons and a wonderful wife, with so much going on outside of myself, not to mention a world that appears to be falling apart at the seams, I am less and less interested in looking inward. My father now gone, I’m ready to be a part of something bigger. I guess I’ve always wanted that, but for most of my life I think it was mostly in efforts to prove to myself that I was worthy of a place in the conversation.

I realize now it has nothing to do with worthiness. It’s about belief. It’s about feeling a sense of urgency to share experience and reflections with others, to learn and to grow productively, consciously, wholly. To ask questions that need to be asked in novel ways that inspire new ways to find answers.

When I was younger I was always willing to take risks that endangered my physical safety or health if they excited me, making terrible decisions that led to great stories, but that also could have ended very differently. I realize now that it wasn’t confidence and optimism that allowed me to take those risks, but rather because beneath the surface I felt there was so little to protect that there was literally nothing to lose. Now, with so much filling my life, my awe-inspiring wife who empowers me to be my best self and never hesitates to call me out when I'm doing something stupid (maybe this letter is one of those moments, but occasionally I still stray from her admonishments). Our boys, whose lives are unfolding before us, eliciting such joy, such pride, such awe. My mother, who has not been featured much in this story, has always offered her unwavering love and support, and, despite some periods of great despondency caused by not knowing what to do to help me, deserves tremendous credit for helping me make it to this point.

Thank you for taking this time with me and allowing me to share.

With deep gratitude,

Michael Stuart Gaillard, Jr.